Musical Mirror

philosophical and poetic thoughts on music

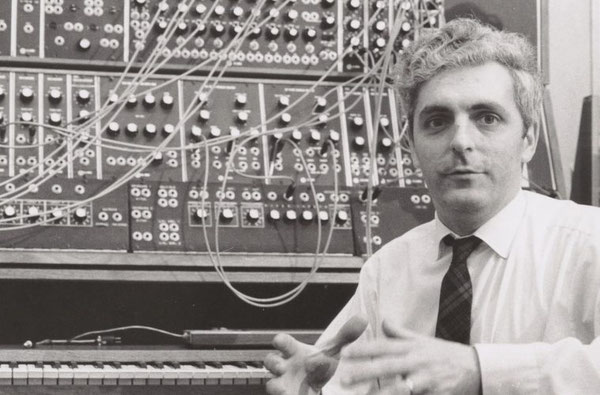

How Robert Moog Changed Music Forever

The Birth of a Sound Revolution

Robert Moog:

The first composer I began working with was Herb Deutsch in 1964. At that time Herb was working with experimental tape recording. He was making music that consisted primarily of tone color changes rather than conventional pitch and melody. He was interested in developing ways of making new sounds, sounds that had textures and qualities that hadn’t been heard before.

The first instruments that we made for him were very experimental. They were made on what electrical engineers call a breadboard. It was a circuit board that i could solder components onto, right out in the open, without any cabinet, fancy power supply or anything.

There were two instruments, one called a voltage-controlled oscillator and the other, a voltage-controlled amplifier.

Let me first explain what an oscillator is. An oscillator produces and electronic signal that repeats regularly between 20 and 20,000 time a second, which we hear as a pitched tone. An amplifier simply makes a sound stronger or weaker. A voltage-controlled oscillator produces a pitched tone whose pitch can be changed rapidly by changing the voltage. Imagine my taking two voltage-controlled oscillators, one of which is going fast enough for us to hear as a pitch, and the other going much slower. I used the second oscillator to control the first oscillator. This would enable me to create a sound whose pitch changes rapidly, like a siren, or a trill, or any one of a great variety of new sounds.

This is exactly what Herb Deutsch proceeded to do. He took voltage-controlled oscillator and voltage-controlled amplifiers, and put them together in ways that we just didn’t foresee, and came up with the most amazing variety of sounds! He was tickled because these were the sounds he had been looking for, but couldn’t obtain with conventional electronic equipment of the early sixties. I was tickled because he was doing something with the circuitry that was familiar to us that had never been done before to our ears.

After Herb and I tried out these two basic modules, which are now very common, we talked about how we would control them, how we would turn the sound on and off. Up until then, Herb would just stick a wire in to make a sound, or turn a switch on. Of course, that’s not how musicians work. Herb and I discussed a few possibilities.

We talked about whether or not to use a conventional music keyboard or should we have a whole bunch of buttons to push, or something that you could slide your hand along to change the pitch continuously like a trombone slide or violin bow.

We decided to use a standard keyboard because it was readily available, and provided an inexpensive way of turning on and off notes and sounds. The first keyboard we built used an organ keyboard mechanism, along with some circuitry that would open and close the voltage control amplifier every time you pressed a key, which made and envelope on the sound.

You could adjust how fast the sound built up by holding the attack, and how fast the sound would decay by manipulating the decay.

The envelope generator inside the keyboards opened up the voltage-controlled amplifier every time you pressed a key, and that is how the sound was shaped.

By the summer of 1964, these were the components that we had assembled, the voltage-controlled oscillators, the voltage-controlled amplifiers, and the keyboard controller.

It was these handmade experimental components that I showed at the Audio Engineering Society Convention in New York City, in the fall of 1964. That was the beginning. During that show in New York, I got my first orders for electronic music components. These were modular components, because each of the components did one thing, and one thing only towards generating, shaping, or controlling sound.

In order to make a complete musical sound; you had to mix several of the components together.

The first circuits were quite basic, actually.

The only problem was that the pitch wasn’t very accurate in the early prototypes. That didn’t bother us at the time, because we were working with composers who didn’t care that much about pitch accuracy.

My first synthesizer customer was the choreographer Alwin Nikolais. He composed all his music on tape, and wanted additional sonic resources. My second customer was Eric Siday, who was doing very well as a composer of radio and TV commercial music.

Only after our synthesizers became commercially important and our customers wanted to produce conventional melodies did we realize that we would have to improve and stabilize our voltage-controlled oscillators.

Vladimir Ussachevsky, who in 1964 was the head of the Columbia—Princeton Electronic Music Center in New York City, gave us an order. He wanted me to design and build an envelope generator that had four parts to the envelope, the initial rise, or attack, the initial fall, or decay, a flat area called sustain, and when you let go of the keyboard or trigger, the fall back to silence, which is called the release. This four part envelope, attack, decay, sustain, release, is now well know to all electronic musicians who play synthesizers. It’s called ADSR envelope. Back then, it was something brand new, an idea Ussachevsky developed for us to design and build.

The last module I want to mention is the voltage-controlled filter, which was ordered by Gustav Ciamaga from the University of Toronto in 1965. This filter is a device that emphasizes or attenuates, (cuts down) various parts of a musical sound, what we call the over-tones. In doing so it actually changes the tone color without changing the pitch or the loudness. The voltage controlled filter allowed the tone color changes in the sound to be affected rapidly, and analog synthesizers are distinguished more for their control filter capabilities that any other single function.

from 'Electronic Music Pioneers' by Ben Kettlewell

https://archive.org/details/electronicmusicp0000kett/mode/2up